Map Of The Runaway Scrape

The Texas Revolution is defined by its battles—the siege of the Alamo, the massacre at Goliad, the 18-minute Battle of San Jacinto that sealed the Texian victory. But in that location was a slower struggle that moisture spring of 1836 that divers the revolution's civilian strife. Equally Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna amassed troops across the Rio Grande, Texian rebels and noncombatants fled the looming disharmonize.

This eastward frantic flight from Mexican troops, toward the Sabine River—which separates Texas from Louisiana—and the prophylactic of the United States, came to exist known as the Runaway Scrape.

"The Runaway Scrape touched well-nigh every citizen in Texas," says Stephen L. Hardin, professor of history at Abilene's McMurry University, describing the exodus as the great untold story of the Texas Revolution. "I think the Delinquent Scrape, far more than the battles, played a major role in the forging of the Texian character.

"It is tremendously of import because if you look at the Texas mythos—Texans are tough, Texans are resilient, this notion that nosotros can endure damn most anything because we're Texans. I think that's where information technology starts."

Colonists began their flight from disharmonize well ahead of the fall of the Alamo in March 1836, and for some of them, the escape culminated within a mile of the San Jacinto battleground site in a dramatic crossing of the San Jacinto River. There, 5,000 settlers waited their plow at Lynch's Ferry, drastic to outrun Santa Anna and his approaching troops.

A sculpture by J. Payne Lara at the San Felipe de Austin Country Historic Site depicts a family fleeing in the Delinquent Scrape.

Julia Robinson

Virtually the time of the fall of the Alamo, Hardin says, the Delinquent Scrape "goes into hyperdrive." Sam Houston and his modest, inexperienced army began a retreat from Gonzales, where the regular army had been gathering. The order to evacuate came at midnight March 13, and the Texians burned the town earlier they left.

As Houston continued his retreat, many of the 30,000 residents of Texas—including Anglos, enslaved people and Mexican nationals—fled Santa Anna's ground forces in the rain and cold, carrying what possessions they could on dingy roads and beyond flood-swollen rivers. In an April 1836 letter to a friend, colonist John A. Quitman remarked, "We must have met at least 1,000 women and children, and everywhere along the road were wagons, article of furniture and provisions abandoned."

Dilue Rose Harris was 11 when she fled her dwelling house in Stafford's Point, just southwest of what is today Houston, with her family unit. In 1898 she wrote of her memories of the Delinquent Scrape: "Nosotros left domicile at dusk. Hauld beding clothing and provision on the sleigh with one yoak of oxin. Mother and I walking she with an infant in her artillery."

Guy Bryan, a nephew of Stephen F. Austin, was 16 when he fled his dwelling well-nigh San Felipe de Austin with his family. He told his story in an 1895 letter of the alphabet to Kate Terrell, a survivor of the Runaway Scrape and writer who chronicled the result. "Some families left their dwelling with their table spread for the daily meal; all hastily prepared for flying as if the enemy were at their door," he wrote.

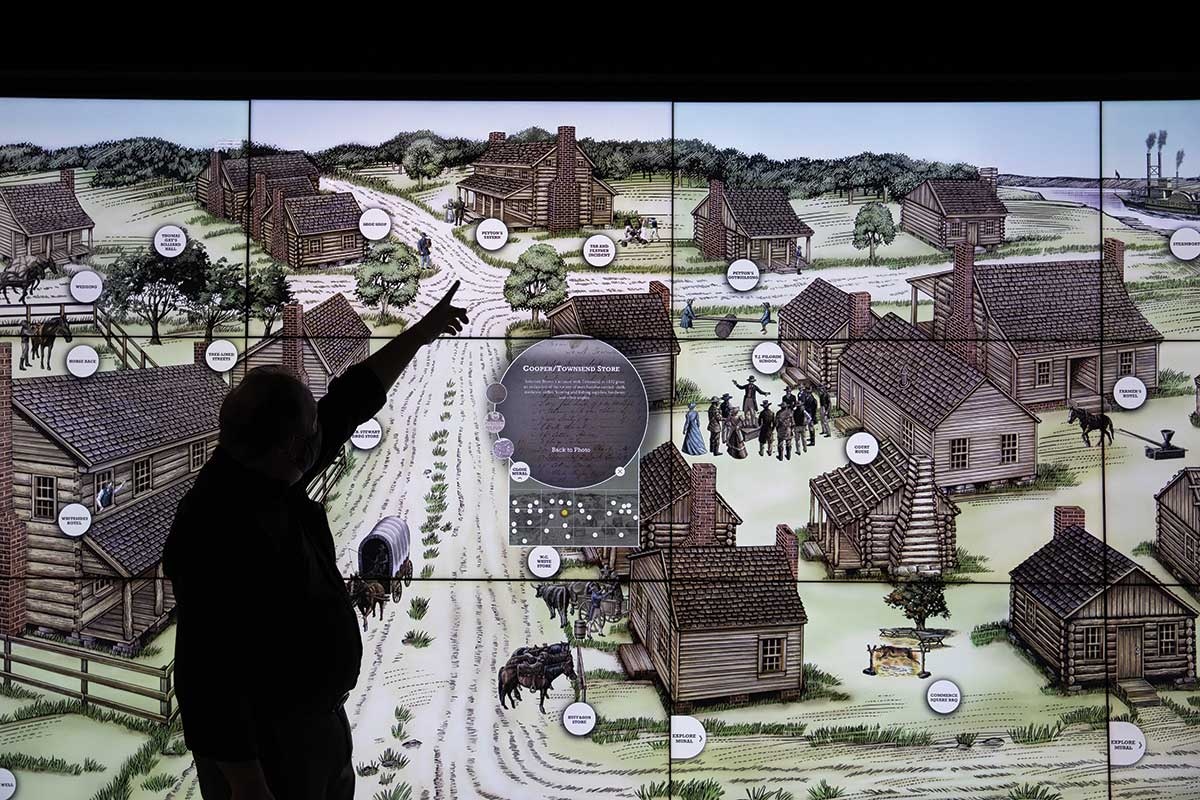

The historic site's museum features an interactive map of the 19th-century boondocks.

Julia Robinson

The 2d-largest city in Texas on the eve of the revolution, San Felipe had shut to 600 residents and was a humming center of government and commerce. As in the town of Gonzales, the Texians and their army burned the town behind them, a strategy to deny Santa Anna's troops food and supplies.

Angelina Peyton Eberly, a tavern owner, recalled in a letter to a friend the evening she evacuated San Felipe beyond the Brazos River: "Much was left on the river banks. In that location were no wagons hardly … few horses, many had to go on foot the mud up to their knees—women and children pell mell." Safely beyond the river, Eberly could hear "the popping of spirits, powder &c [etc.] in our called-for homes."

Creed Taylor, a Texian soldier who escorted his family to condom earlier fighting in the Battle of San Jacinto, wrote in 1900, "I have never witnessed such scenes of distress and human suffering. … Frail women trudged alongside their park horses, carts, or sleds from day to day until their shoes were literally worn out, then connected the journeying with bare feet, lacerated and bleeding at most every footstep. Their apparel were scant, and with no means of shelter from frequent rains and bitter winds, they traveled on through the long days in moisture and bedraggled clothes, finding even at dark little relief from their suffering since the moisture earth and angry sky offered no relief. … Thus these half-clad, mud-besmeared fugitives, looking like veritable savages, trudged along."

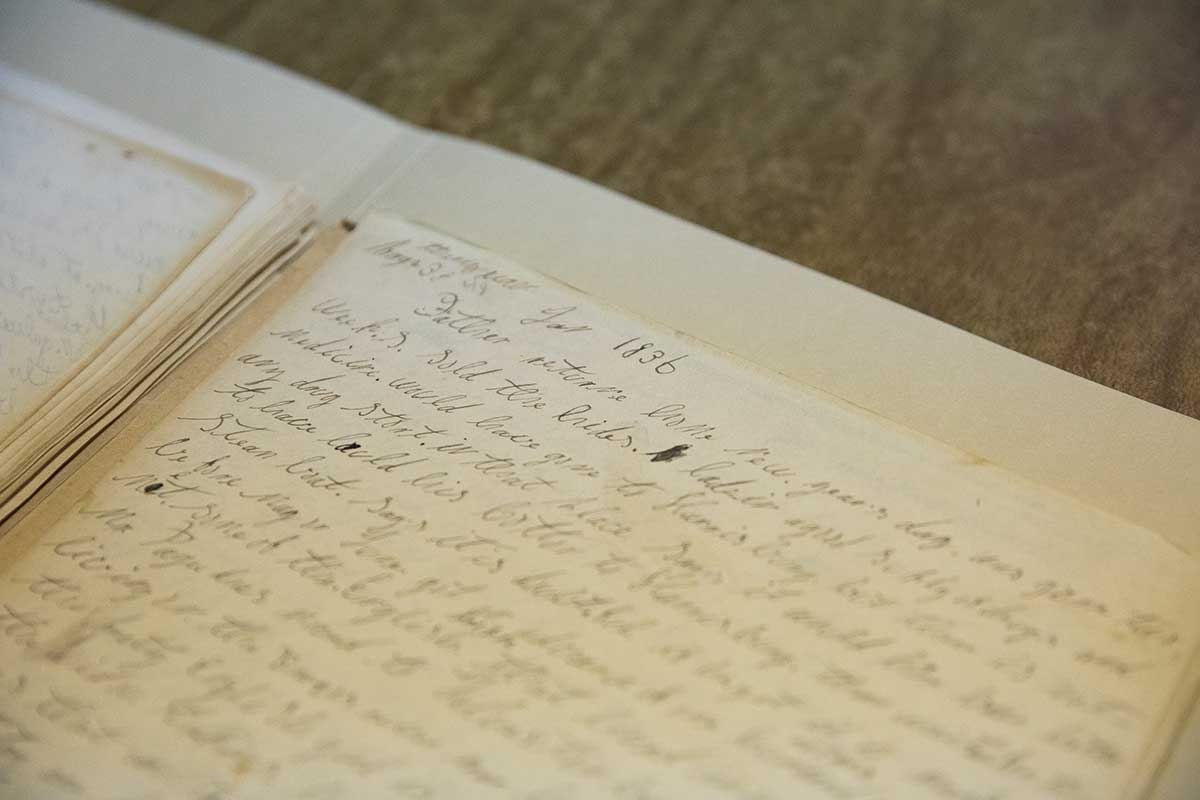

Dilue Rose Harris' memoirs are at the Albert and Ethel Herzstein Library in the San Jacinto Museum of History in La Porte.

Julia Robinson

Harris, Bryan and Eberly converged with other refugees at Lynch'due south Ferry, on the southward bank of the San Jacinto River, within a mile of the future battleground at San Jacinto. "Arrived at the San Jacinto River in the night," wrote Harris. "There were fully v,000 people at the ferry. … We waited iii days earlier we crossed. … Information technology was all-well-nigh a riot to see who should cantankerous first."

The crossing was daunting. The ferry was a wooden, flat-bottomed raft, hand-fatigued along cables. A few dozen people and possessions could travel per trip.

After crossing the ferry at Lynchburg, Bryan and his party moved 6 miles southeast. "When nosotros joined the long line of 'Runaways' at Cedar Bayou the sight was virtually piteous. I shall never forget the sight of men, women and children walking, riding on horseback, in carts, sleds, wagons and every kind of transportation known to Texas."

Many families in the Runaway Scrape passed through what is at present the San Jacinto Battlefield State Historic Site.

Julia Robinson

Many became ill or died along the route. There are no official records of deaths, simply historians estimate hundreds died. "Measles, sore eyes, whopping coughing, and every other disease that human, woman or child is heir to, bankrupt out amongst us," wrote Harris. Her younger sis died of a flux—diarrhea—and was buried at Freedom. With scant updates, families kept moving east, toward the Sabine River and the condom of the United States.

Harris recalled one evening: "All of asddnt we heard a written report like afar thunder. … Begetter said information technology was cannon that the Texas army and Mexicans were fighting." They idea the Texians had lost because the cannon fire ended then quickly. They hurried eastward until a messenger institute them and yelled, every bit Harris wrote, "Plough back, plough back. The Texas ground forces has whipped the Mexicans. No danger, no danger."

Relieved but wearied, many halted their exodus. Refugee camps sprang up for families to balance and regroup. "They suffered merely as much and sometimes more on the return trip," Hardin says. Many returned to find their homes burned and their livestock missing.

Harris' memoirs retrieve quicksand and a fatal alligator attack when they turned back toward home after five weeks on the run. Eberly had traveled more 100 miles earlier hearing of the victory at San Jacinto. Once dorsum in San Felipe, Eberly found her tavern and home in ashes, "the place bare of everything but the ruins of all my things burnt upward," she wrote. Many residents, including Eberly, abandoned San Felipe de Austin, which never regained its erstwhile stature. Many left Texas for good after the spring of 1836. For those who stayed, the scrape left a scar.

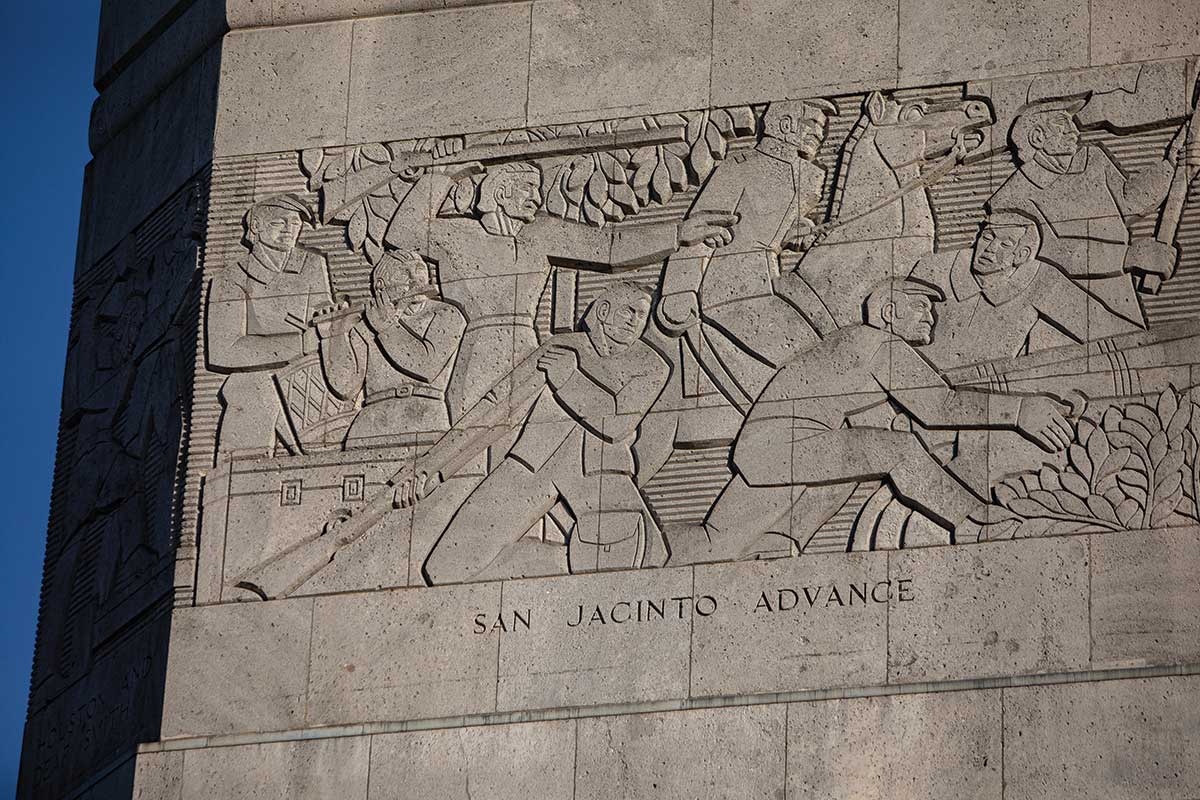

A frieze on the San Jacinto Monument.

Julia Robinson

Hardin explains that many Texians were hesitant to rebuild later the state of war. "I've found many people saying they don't desire to invest in a fancy house because the Mexicans might invade over again, and we're going to have to burn information technology down once again," he says. "So that plays a huge office in the Texian psyche for years because they simply didn't accept the confidence.

" 'Call up the Alamo'? What they're remembering is the Runaway Scrape and the hardship."

Julia Robinson is a photojournalist in Austin. See more than of her work at juliarobinsonphoto.com.

Map Of The Runaway Scrape,

Source: https://texascooppower.com/the-runaway-scrape/

Posted by: murraynessittere.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Map Of The Runaway Scrape"

Post a Comment